A Million Tons of Copper Is on the Way: It May Not Be Enough

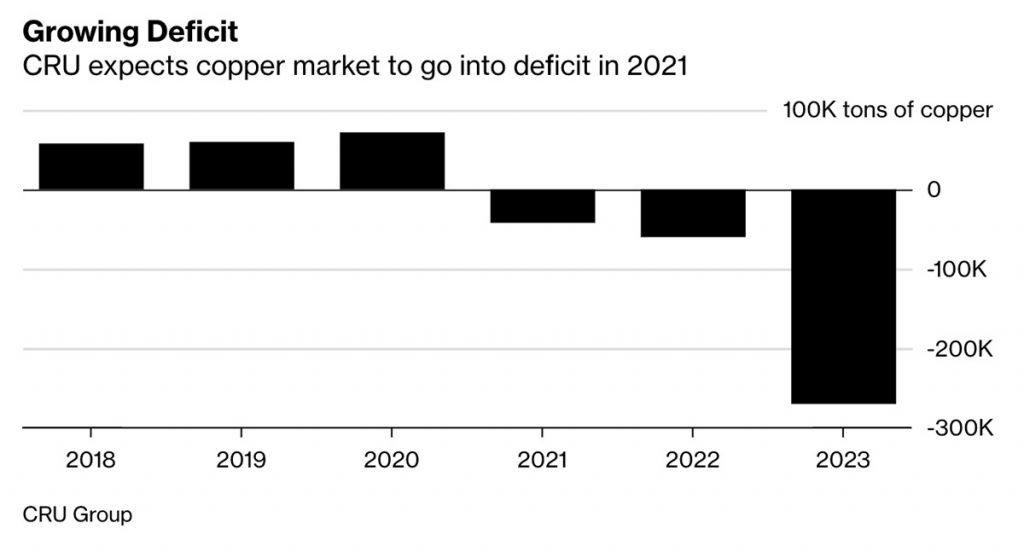

Giant mines currently under construction will churn out an additional 1 million tons of copper through 2023, but that won’t be enough to fully close an expected gap between supply and demand in the next few years.

Industry analysts and executives descending on Santiago this week for the Cesco conference, one of the industry’s biggest events, are in bullish spirits: a key indicator of the market for semi-processed copper ore — known as concentrates — is pointing to the tightest market in more than five years, and banks and brokers such as Morgan Stanley and Macquarie Group Ltd. rank the metal as one of their top picks.

“We are looking at a classic resource cycle,” said Colin Hamilton, managing editor for commodities at BMO Capital Markets. “No one has copper coming now, when it is needed, but everyone has projects coming 2022-2023 –- potentially after we’ve had to drive some substitution.”

Copper futures traded in New York reached the highest in more than three years at the end of 2017. Shortly after that, large copper projects that had been on hold since a downturn in 2016 moved into construction phase.

Anglo American Plc has started building its Quellaveco mine in Peru, which will begin ramping up in 2022, and Teck Resources Ltd. has announced its Quebrada Blanca expansion in Chile will start producing in 2021. The two mega projects join First Quantum Metals Ltd.’s Cobre Panama mine, which has started producing this year.

As a result CRU Group, which runs the main conference during Cesco Week, has cut its deficit forecast and now expects the market will be in a small surplus this year and next. The researcher forecasts a 270,000-ton short by 2023.

“Prices were higher at the beginning of last year, and as a result of that a lot of board approvals came through,” said Vanessa Davidson, CRU’s director of copper. “Because we’ve seen lower prices since then, a lot of people have started to hold back.”

The outlook for the deficit is helping underpin prices even as concern mounts over a slowing global economy and persistent trade frictions. The metal is expected to end the year at about $2.86 a pound, near the current $2.93, and to remain largely unchanged for the next two years, Davidson said. The price is forecast to reach $3.30 in 2023, according to CRU.

A decline in copper prices from last year’s high has slowed development of additional projects needed to fill the shortfall. It will probably take higher prices for boards to approve additional projects, Davidson said.

“I think projects are going to get approved at around $3.20, or something like this,” Davidson said. “When that happens, we could see again a lot of people going ahead with projects.”